Curbing Security Council vetoes

Since the founding of the United Nations seventy years ago, five states—China, France, Russia, the United States, and the United Kingdom, often referred to as the P5—have wielded a so-called “veto power”. Veto power means that whenever the UN Security Council votes on a resolution—to apply an arms embargo on North Korea, to create a peacekeeping mission in Darfur, or authorize sanctions on South Sudan, etc.—these five countries individually have the power to stop the resolution from going forward. A veto scuttles the chances for any collective and legal international action to address situations which concern all of humanity—whether they be a potential future genocide in Myanmar, Kim Jong-un’s terrorization of his population, and recurrent war crimes in Gaza.

The inclusion of a veto power in the UN Charter was meant to ensure buy-in to the new international body from the victors of World War II. Indeed, many argue that the Soviet Union and the United States would not have joined the UN without possessing such power. To be sure, without the assurance of a veto for the U.S. and the Soviet Union, it is possible that the UN may have gone the way of the League of Nations by not surviving the Cold War.

However, simply because a system served a purpose once does not mean that we should allow it to continue unchanged today. Due to the vetoes exerted or threatened by the P5, the UN has been unable to react as the Syrian death toll climbs above 210,000. The international community has been immobilized to respond to evidence that North Korea is responsible for systematic crimes against humanity against its own people. War crimes can be committed with impunity in Gaza, on a recurrent basis, without fear that the Security Council will hold its perpetrators to account. Rohingya Muslims, with the full knowledge that the Security Council will never even meet to address their plight, have been brought to the brink of genocide.

Nor are these, as some might argue issues of only domestic concern. The refugee crisis and spread of terrorism among Syria and Palestine’s neighbors, the Rohingya migrant crisis affecting Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia, and Kim Jong-un’s systematic abduction of foreign nationals make it clear that these atrocity crimes destabilize the world at large. If the Security Council, due to the veto power of the P5, cannot address issues of such magnitude, then it has become unable to fulfill its primary function of maintaining international peace and security. Something must change—atrocities left unaddressed cannot become the new normal.

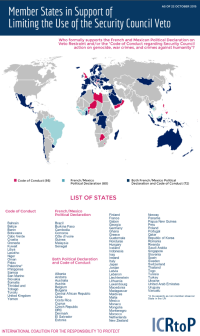

If we want to see a Security Council that acts to prevent and respond to atrocity crimes and subsequently succeeds at its mandate, it is imperative for governments to offer their support for the new “Code of Conduct” on Security Council action against genocide, crimes against humanity, or war crimes. The Accountability, Coherence, and Transparency (ACT) Group, a grouping of UN Member States working to improve the working methods of the Security Council, put forth the Code, in which signatories “pledge to not vote against a credible draft resolution aimed at preventing or ending the commission of genocide, crimes against humanity or war crimes.” The Code will be officially launched on the 70th anniversary of the United Nations on 23 October 2015.

If we want to see a Security Council that acts to prevent and respond to atrocity crimes and subsequently succeeds at its mandate, it is imperative for governments to offer their support for the new “Code of Conduct” on Security Council action against genocide, crimes against humanity, or war crimes. The Accountability, Coherence, and Transparency (ACT) Group, a grouping of UN Member States working to improve the working methods of the Security Council, put forth the Code, in which signatories “pledge to not vote against a credible draft resolution aimed at preventing or ending the commission of genocide, crimes against humanity or war crimes.” The Code will be officially launched on the 70th anniversary of the United Nations on 23 October 2015.

The Code is complementary to another initiative currently underway at the United Nations, a political declaration spearheaded by France and Mexico. The political declaration focuses on securing a voluntary agreement among the P5 members of the Council to restrain from using the veto in situations of mass atrocities.

Interestingly, under the ACT code, such an obligation does not rest solely with the P5. Rather all elected Council members who sign the pledge would also be bound to not obstruct such resolutions. The pledge recalls that governments have already acknowledged, in the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document, that they had a Responsibility to Protect (RtoP, R2P) populations from such crimes.

In a matter of weeks, the Code has received 97 signatories, including 2 members of the P5 (France and the UK), while the political declaration also has 80 number of signatories, with France being the sole P5 member currently on the list. As codes and declarations, they will be non-binding on their signatories, which may lead many to scoff that they have no utility at all. But change in the international system is always incremental. Building international consensus that it is shameful to use the veto in situations of atrocities—and ratcheting up the political pressure on those who do—is a first step towards building a better Security Council, and in the meantime a better and faster response to atrocities.

This article was originally published on the ICRtoP online blog.

Sign up for our weekly updates to get the latest #GlobalJustice news.