Justice for the Rohingya: What has happened and what comes next?

For decades, the Burmese military and State – most recently under the auspices of Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi’s government – have been consciously and systematically violating the fundamental human rights of the Rohingya population in Myanmar. One of the most striking denials is that of citizenship: the Rohingya are not recognised in Myanmar as an ethnic group and most are unable to produce the paperwork required for the most basic level of citizenship due to decades of discrimination and repression. Because of this, most Rohingya are effectively stateless, which means a whole host of rights are unavailable to them, including the right to vote, study, work, travel, marry, practice their religion and access health services.

Since the 2017 military crackdown, in which human rights abuses and a vast array of atrocities were committed, 720,000 Rohingya people have fled to Bangladesh, where they have been living in refugee camps in unsustainable conditions. It is estimated that another 100,000 are internally displaced, confined in camps within Myanmar. Burmese Rohingya have been subject to mass killings, sexual and gender-based violence and other atrocities, to the extent that UN Secretary-General Guterres defined them as “the most persecuted minority in the world”.

The legal situation(s) background

In November 2019, The Gambia took on the Rohingya case on behalf of a larger collective of States, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), by bringing genocide allegations before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and seeking provisional measures directed towards ending the genocide, punishing those who commit it and protecting and preserving relevant evidence. Over at the International Criminal Court (ICC), Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda requested authorisation to initiate an investigation into the situation of Bangladesh/Myanmar over alleged crimes against humanity in July 2019. Meanwhile, in Argentina, a universal jurisdiction case has been filed by Tun Khin, President the Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK, alleging serious crimes including genocide against the Rohingya. These three cases came together in a “perfect storm” in November 2019, raising hopes that justice might be becoming more of a reality for the Rohingya. This post will focus on the two cases within international jurisdictions, but it is worth recalling that the road to justice will be long and the more accountability options that can be activated, the more likely it is that road will lead to eventual success for the Rohingya.

One situation for two Courts

The International Court of Justice (ICJ)

The ICJ, the UN’s principal Court, has jurisdiction over disputes between States about UN Treaties and binding legal instruments. In November 2019, The Gambia filed a contentious case against Myanmar, claiming that Myanmar had failed to comply with its international obligations under the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Genocide Convention), which Myanmar ratified in 1956 and The Gambia acceded to in 1978. The case is historical, since it is the first time a State has brought a genocide case before the ICJ when it was not directly involved in the alleged genocide.

Both parties made oral submissions at the ICJ in December 2019. Myanmar’s Aung San Suu Kyi claimed that while there may have been war crimes, there had been no genocide; according to Myanmar, the 2017 Burmese military action had been solely aimed at calming down social unrest in Rakhine state. Tellingly, no member of Myanmar’s legal team referred to the Rohingya by name: the only time they uttered the word “Rohingya” was in the context of claims that counter-insurgency operations were necessary due to attacks launched by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army. The Gambia, by contrast, provided large amounts of information detailing the long-standing persecution and repression of the Rohingya and the genocidal acts committed against them, including mass killings, torture, burnings and sexual and gender-based violence. In their opening statement, The Gambia’s Minister of Justice Aboubacarr Marie Tambadou said “All that The Gambia asks is that you tell Myanmar to stop these senseless killings, to stop these acts of barbarity and brutality that have shocked and continue to shock our collective conscience, to stop this genocide of its own people”.

On 23 January 2020, the ICJ released its landmark decision on provisional measures. Endorsed unanimously by all 17 judges, the binding decision orders Myanmar to act promptly to prevent further abuses and human rights violations against Rohingya population; to avoid the destruction or damaging of evidence related to the case; and to report regularly to the ICJ on actions undertaken to reach these objectives, initially at 4 months then every 6 months after that. The provisional measures are the latest development within the ICJ framework. Now the hard work of building the case of genocide for the eventual hearing on the merits is beginning, for which initial pleadings are due by The Gambia on 23 July 2020 and by Myanmar on 25 January 2021.

The International Criminal Court (ICC)

As for the ICC, the court of last resort established by the 1998 Rome Statute, matters are slightly different. Unlike the ICJ, the ICC does not adjudicate on States but on individuals, with jurisdiction over the international law violations listed in the Rome Statute, including war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide. Absent a UN Security Council Resolution or referral by a State of crimes committed in its own country, the ICC only has jurisdiction over crimes allegedly committed by the national of a State Party or on the territory of a State Party, which Myanmar is not. In this framework, the Rohingya case involves crimes falling within the jurisdiction of the ICC, particularly the crime against humanity of deportation, and perpetrated against Burmese Rohingya population that ended in Bangladesh, even if they started in Myanmar. On 14 November 2019, ICC judges authorised the Prosecutor to open investigations, having received her request to do so in July and having heard views from hundreds of thousands of alleged victims.

As noted, this situation is peculiar in that while Bangladesh is a party to the Rome Statute, Myanmar is not. In the usual course of events, acts committed in Myanmar would not be admissible before the ICC, as they would fall outside its jurisdiction. In this case, however, the Court has authorised the investigation “with broad parameters”, on any crimes “committed, at least in part, on the territory of Bangladesh (or any other State Party or State formally accepting the jurisdiction of the ICC), insofar as the crimes are sufficiently linked to the situation, and irrespective of the nationality of the perpetrators”, as explained last week by Phakiso Mochochoko, Director of the Jurisdiction, Complementarity and Cooperation division at the ICC. On this basis, the ICC Office of the Prosecutor is currently in the process of organising a fact-finding mission to gather relevant evidence and build their case(s).

What now?

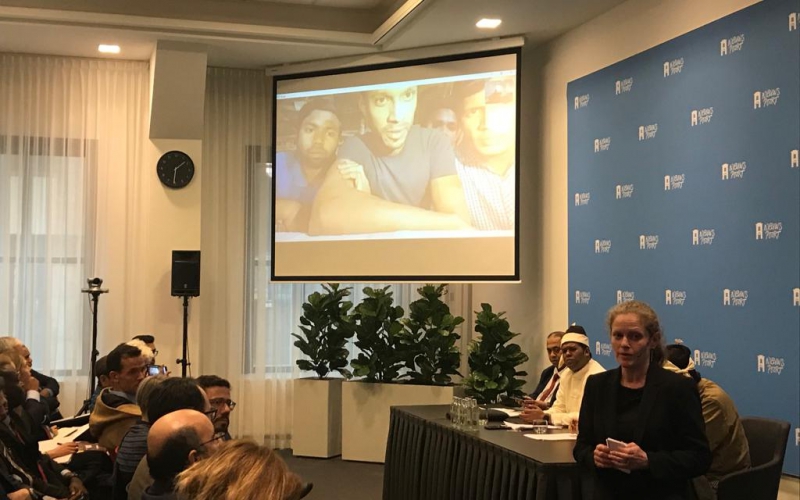

The ICJ decision has been a reason of joy for the Rohingya worldwide and a clear message that such gross and systematic human rights violations should not go unnoticed or unpunished. In a panel discussion on Rohingya perspectives hosted by No Peace Without Justice and partner NGOs immediately after the release of the order for provisional measures, Rohingya activists expressed their satisfaction and optimism for this partial but significant victory, calling for the momentum not to fade away. Significantly, the ICJ recognised the Rohingya as a protected group under the Genocide Convention, prompting Mayyu Ali, Rohingya Author and Poet, to tweet “Oh Wow: My #Rohingya people and me are protected under the Genocide Convention, the ICJ concludes now”.

Myanmar, however, continues to stand in firm denial of any genocidal intent towards the Rohingya population, claiming they are carrying out their own investigation on the 2017 incidents through the domestic Independent Commission of Enquiry (ICOE). Just before the release of the ICJ’s decision on provisional measures, the ICOE had issued a report on the situation, stating that, while it acknowledges that war crimes might have been committed, no genocidal intent has been found – a clear attempt to render the ICJ allegations ill-founded. Rohingya activist Yasmin Ullah defined this move as “the new media strategy” implemented by Suu Kyi’s government in order to get away with committing atrocities.

In the meantime, Rohingya population is still discriminated against and targeted by Myanmar military forces, despite the provisional measures issued by the ICJ. The chief commander of the Burmese army reported that regarding these measures, Myanmar will apply the existing laws – namely, the ones which created this situation in the first place. In January, Myanmar also denied access to UN Special Rapporteur on Myanmar Yanghee Lee, who was forced to carry out her fact-finding mission from Thailand and Bangladesh.

So, despite what the ICJ decision means to the Rohingya, the challenge will be to ensure Myanmar actually complies with the order and that the international community is galvanised to encourage them to do so, starting with the UN Security Council despite its failure to do so when presented with the opportunity in early February 2020. As far as the ICC situation is concerned, it will likely take a significant time to complete their investigations and build cases against individual perpetrators of the crimes in question. There continue to be challenges for the ICC in terms of its ability to connect effectively with victims and populations affected by the crimes, meaning they will need to step up outreach efforts for the Rohingya.

Despite these challenges, current developments in both Courts are highly significant, especially for their symbolic force. There is hope that cases at the ICJ and ICC and elsewhere will finally result in justice for the Rohingya, ensuring accountability for perpetrators and redress for victims. For now, at least, the message is clear: human rights violations and crimes against humanity will not be glossed over. Constant commitment and common efforts are now needed so that they will not remain unpunished.